Pengguna:Aimwin66166/Kotak pasir/Kebergantungan kereta

Kebergantungan kereta ialah konsep dimana pelan rekabentuk sesebuah bandar yang menggalakkan penggunaan kereta berbanding kaedah pengangkutan yang lain, seperti basikal, pengangkutan awam, serta berjalan kaki.

Ringkasan

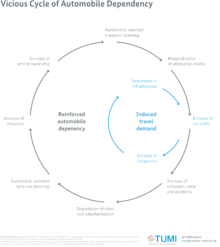

suntingDi kebanyakkan bandar moden, kereta adalah mudah dan seringkali menjadi keperluan bagi memudahkan pergerakkan.[1] Bagi penggunaan kereta, wujudnya sebuah kesan yang berterusan dimana kesesakan trafik menghasilkan 'permintaan' bagi jalan raya yang lebih besar dan banyak serta penghapusan objek yang menghalang aliran trafik yang lancar. Sebagai contoh, pejalan kaki, lintasan pejalan kaki, lampu isyarat, penunggang basikal, dan pelbagai bentuk pengangkutan awam seperti trem.

Tindakan ini mengakibatkan penggunaan kereta lebih mudah dan cepat, namun kaedah pengangkutan lain terkesan dengan negatif, oleh itu volum lalu lintas yang lebih tinggi tercetus.

Tambahan pula, rekabentuk urban bandar beradaptasi kepada keperluan kereta dari segi pergerakkan dan ruang. Contohnya, bangunan digantikan oleh tempat letak kereta. Jalan beli-belah terbuka digantikan oleh pusat beli-belah tertutup. Pusat bandar dengan pelbagai fungsi pusat komersial, peruncitan, dan hiburan digantikan oleh pasaraya besar, kompleks hiburan gergasi yang masing-masing dikelilingi tempat letak kereta yang meluas.

Persekitaran seperti ini memaksa orang ramai untuk menggunakan kereta untuk mengakses kawasan seperti ini, lalu mencetuskan lebih banyak trafik keatas ruang jalan raya. Kesannya ialah kesesakan trafik dan kitaran tersebut akan berulang, dimana jalan raya diluaskan dan memakan lebih banyak ruang yang boleh digunakan bagi kawasan perumahan, kilang serta pelbagai lagi kegunaan yang berguna dari segi ekonomi dan sosial. Penangkutan awam juga menjadi lebih sukar digunakan dan menjadi stereotaip bagi kemiskinan serta warga asing, lalu menjadi kaedah pengangkutan minoriti. Akhirnya, kebebasan serta pilihan penduduk untuk menikmati kehidupan tanpa mengguna kereta berkurangan. Bandar seperti itu dikatakan sebagai bergantung kepada kereta.

Kebergantungan kereta dilihat sebagai isu bagi kelestarian alam sekitar kerana penggunaan sumber tidak boleh diperbaharui dengan tidak efisen serta pembebasan gas rumah hijau yang bertanggungjawab keada pemanasan global. Selain itu, kebergantungan kereta juga merupakan isu kelangsungn sosial dan budaya. Umpama komuniti berpagar, kereta persendirian menghasilkan pengasingan fizikal antara manusia dan mengurangkan interaksi sosial antara manusia yang merupakan aspek signifikan bagi membina jaringan sosial dalam kawasan bandar.

Origins of car dependency

suntingCar dependency saw its formation in the direct aftermath of the Second World War.[2] The resultant economic and built environment restructuring allowed wide adoption of automobile use. In the United States, the expansive manufacturing infrastructure, increase in consumerism, and the establishment of the Interstate Highway System set forth the conditions for car dependence in communities.

Urban design factors

suntingLand-use (zoning)

suntingIn 1916 the first zoning ordinance was introduced in New York City, the 1916 Zoning Resolution. Zoning was created as a means of organizing specific land uses in a city so as to avoid potentially harmful adjacencies like heavy manufacturing and residential districts, which were common in large urban areas in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Zoning code also determines the density of housing allowed in certain areas of a city by defining such things as single-family homes, and multi-family residential as being allowed as of right or not in certain areas. The overall effect of zoning in the last century has been to create homogenized zones in cities that had previously been a mix of heterogenous residential and business uses. The problem is particularly severe right outside of cities, in ring suburbs where strict zoning codes almost exclusively allow for single family detached housing. [3] Strict zoning codes that result in a heavily segregated built environment between residential and commercial land uses contributes to car dependency by making it nearly impossible to access all one's given needs, such as housing, work, school and recreation without the use of a car. One key solution to the spatial problems caused by zoning would be a robust public transportation network. There is also currently a movement to amend older zoning ordinances to create more mixed-use zones in cities that combine residential and commercial land uses within the same building or within walking distance to create the so-called 15-minute city.

Parking minimums are also a part of modern zoning codes, and contribute to car dependency through a process known as induced demand. Parking minimums require a certain number of parking spots based on the land use of a building and are often designed in zoning codes to represent the maximum possible need at any given time.[4] This has resulted in cities having nearly eight parking spaces for every car in America, which have created cities almost fully dedicated to parking from free on-street parking to parking lots up to three times the size of the businesses they serve.[4] This prevalence in parking has perpetuated a loss in competition between other forms of transportation such that driving becomes the de-facto choice for many people even when alternatives do exist.

Street design

suntingThe design of city roads can contribute significantly to the perceived and actual need to use a car over other modes of transportation in daily life. In the urban context car dependence is induced in greater numbers by design factors that operate in opposite directions - first, design that makes driving easier and second, design that makes all other forms of transportation more difficult. Frequently these two forces overlap in a compounding effect to induce more car dependence in an area that would have potential for a more heterogenous mix of transportation options. These factors include things like the width of roads, that make driving faster and therefore 'easier' while also making a less safe environment for pedestrians or cyclists that share the same road. The prevalence of on-street parking on most residential and commercial also streets makes driving easier while taking away street space that could be used for protected bike lanes, dedicated bus lanes, or other forms of public transportation.

Negative externalities of automobile

suntingAccording to the Handbook on estimation of external costs in the transport sector[5] made by the Delft University and which is the main reference in European Union for assessing the externalities of cars, the main external costs of driving a car are:

- congestion and scarcity costs,

- collision costs,

- air pollution costs,

- noise pollution costs,

- climate change costs,

- costs for nature and landscape,

- costs for water pollution,

- costs for soil pollution and

- costs of energy dependency.

Addressing the issue

suntingThere are a number of planning and design approaches to redressing automobile dependency, known variously as New Urbanism, transit-oriented development, and smart growth. Most of these approaches focus on the physical urban design, urban density and landuse zoning of cities. Paul Mees argued that investment in good public transit, centralized management by the public sector and appropriate policy priorities are more significant than issues of urban form and density.

Removal of minimum parking requirements from building codes can alleviate the problems generated by car dependency. Minimum parking requirements occupy valuable space that otherwise can be used for housing. However, removal of minimum parking requirements will require implementation of additional policies to manage the increase in alternative parking methods.[6]

There are, of course, many who argue against a number of the details within any of the complex arguments related to this topic, particularly relationships between urban density and transit viability, or the nature of viable alternatives to automobiles that provide the same degree of flexibility and speed. There is also research into the future of automobility itself in terms of shared usage, size reduction, roadspace management and more sustainable fuel sources.

Car-sharing is one example of a solution to automobile dependency. Research has shown that in the United States, services like Zipcar, have reduced demand by about 500,000 cars.[7] In the developing world, companies like eHi,[8] Carrot,[9][10] Zazcar[11] and Zoom have replicated or modified Zipcar's business model to improve urban transportation to provide a broader audience with greater access to the benefits of a car and provide "last-mile" connectivity between public transportation and an individual's destination. Car sharing also reduces private vehicle ownership.

Urban sprawl and smart growth

suntingWhether smart growth does or can reduce problems of automobile dependency associated with urban sprawl has been fiercely contested for several decades. The influential study in 1989 by Peter Newman and Jeff Kenworthy compared 32 cities across North America, Australia, Europe and Asia.[12] The study has been criticised for its methodology,[13] but the main finding, that denser cities, particularly in Asia, have lower car use than sprawling cities, particularly in North America, has been largely accepted, but the relationship is clearer at the extremes across continents than it is within countries where conditions are more similar.

Within cities, studies from across many countries (mainly in the developed world) have shown that denser urban areas with greater mixture of land use and better public transport tend to have lower car use than less dense suburban and exurban residential areas. This usually holds true even after controlling for socio-economic factors such as differences in household composition and income.[14]

This does not necessarily imply that suburban sprawl causes high car use, however. One confounding factor, which has been the subject of many studies, is residential self-selection:[15] people who prefer to drive tend to move towards low-density suburbs, whereas people who prefer to walk, cycle or use transit tend to move towards higher density urban areas, better served by public transport. Some studies have found that, when self-selection is controlled for, the built environment has no significant effect on travel behaviour.[16] More recent studies using more sophisticated methodologies have generally rejected these findings: density, land use and public transport accessibility can influence travel behaviour, although social and economic factors, particularly household income, usually exert a stronger influence.[17]

The paradox of intensification

suntingReviewing the evidence on urban intensification, smart growth and their effects on automobile use, Melia et al. (2011)[18] found support for the arguments of both supporters and opponents of smart growth. Planning policies that increase population densities in urban areas do tend to reduce car use, but the effect is a weak one, so doubling the population density of a particular area will not halve the frequency or distance of car use.

These findings led them to propose the paradox of intensification:

- All other things being equal, urban intensification which increases population density will reduce per capita car use, with benefits to the global environment, but will also increase concentrations of motor traffic, worsening the local environment in those locations where it occurs.

At the citywide level, it may be possible, through a range of positive measures to counteract the increases in traffic and congestion that would otherwise result from increasing population densities: Freiburg im Breisgau in Germany is one example of a city which has been more successful in reducing automobile dependency and constraining increases in traffic despite substantial increases in population density.

This study also reviewed evidence on local effects of building at higher densities. At the level of the neighbourhood or individual development, positive measures (like improvements to public transport) will usually be insufficient to counteract the traffic effect of increasing population density.

This leaves policy-makers with four choices:

- intensify and accept the local consequences

- sprawl and accept the wider consequences

- a compromise with some element of both

- or intensify accompanied by more direct measures such as parking restrictions, closing roads to traffic and carfree zones.

See also

sunting- Accessibility (transport)

- Automotive city

- Car costs

- Car-free movement

- Effects of the car on societies

- Externalities of automobiles

- Fossil fuel lobby

- Forced rider

- Jevons paradox

- Mobile source air pollution

- Peak car

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Sustainable transport

- Transit-oriented development

- Transport divide

- Urban sprawl

- Urban planning

- Cycling infrastructure

Notes and references

sunting- ^ Robinson, Grayson (2021-05-02). "The History Behind Car (In)Dependence in the US vs World". ArcGIS StoryMaps (dalam bahasa Inggeris). Dicapai pada 2021-12-01.

- ^ Robinson, Grayson (2021-05-02). "The History Behind Car (In)Dependence in the US vs World". ArcGIS StoryMaps (dalam bahasa Inggeris). Dicapai pada 2021-12-01.

- ^ Bronin, Sarah (2021). "Zoning by a Thousand Cuts: The Prevalence and Nature of Incremental Regulatory Constraints on Housing". Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy.

- ^ a b Shoup, Donald (2011). The High Cost of Free Parking (dalam bahasa English). New York: Routledge. ISBN 1884829988.CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- ^ M. Maibach; dll. (February 2008). "Handbook on estimation of external costs in the transport sector" (PDF). Delft, February: 332. Dicapai pada 2015-09-20. Cite journal requires

|journal=(bantuan) - ^ Samsonova, Tatiana (25 February 2021). "Reversing Car Dependency". The International Transport Forum. No. 181: 41 – melalui OECD/ITF.

- ^ "Car-Sharing, Social Trends Portend Challenge for Auto Sales".

- ^ eHi

- ^ "Carrot". Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 2018-11-16. Dicapai pada 2018-03-20.

- ^ "Sustainable Cities Collective".

- ^ "Zazcar". Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 2019-10-11. Dicapai pada 2021-05-14.

- ^ Cities and Automobile Dependence: An International Sourcebook, Newman P and Kenworthy J, Gower, Aldershot, 1989.

- ^ MINDALI, O., RAVEH, A. and SALOMON, I., 2004. Urban density and energy consumption: a new look at old statistics. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 38(2), pp. 143-162.

- ^ e.g. FRANK, L. and PIVOT, G., 1994. Impact of Mixed Use and Density on Three Modes of Travel. Transportation Research Record, 1446, pp. 44-52.

- ^ Transport Reviews Volume 29 Issue 3 (2009) was entirely devoted to this issue

- ^ e.g. Bagley, M.N. and Mokhtarian, P.L. (2002) The impact of residential neighborhood type on travel behavior: A structural equations modeling approach. Annals of Regional Science36 (2), 279.

- ^ e.g.Handy, S., Cao, X. and Mokhtarian, P.L. (2005) Correlation or causality between the built environment and travel behavior? Evidence from Northern California. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment10 (6), 427-444.

- ^ Melia, S., Barton, H. and Parkhurst, G. (In Press) The Paradox of Intensification. Transport Policy 18 (1)

Bibliography

sunting- Mees, P (2000) A Very Public Solution:transport in the dispersed city, Carlton South, Vic. : Melbourne University Press ISBN 0-522-84867-2

- Geels, F., Kemp, R., Dudley, G., Lyons, G. (2012) Automobility in Transition? A Socio-Technical Analysis of Sustainable Transport. Oxford: Routledge.